Death of Joseph Cobb

On 13 March 1911, Jack's father, Joseph, celebrated his 70th birthday. Almost immediately his health declined and after a three day illness, he passed away on 17 March. It is likely that Jack and the extended Cobb family gathered together in Napier on the following Sunday to attend the funeral at the Trinity Methodist Church and the burial service at the Old Napier Cemetery.

Coronation of King George V & Queen Mary

Thursday, 22 June 1911 was the day of the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary. It was declared a partial holiday. The town of Te Kuiti held a handful of celebrations to mark the occasion including some special coronation services at some churches, and there were special ceremonies at schools for the children.

Having fun!

It appears that Jack had a great sense of humour and enjoyed having a bit of fun. Here is the autograph he left in his sister, Dorothy's autograph book:

|

Jack left this message in Dorothy Blackman's autograph book 1911.

(Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland 2018) |

On Friday 19 September 1913 Jack attended a 'plain and fancy-dress ball' which was held in Paki Paki, near Hastings. It was a fundraiser for the school prize fund. Many children were in attendance and there were prizes for the best fancy dress for girls, best fancy dress for boys and most original. All those who attended the evening in fancy dress were named in the paper. Jack was mentioned as one of the few adults who dressed up which shows that he must have had a sense of fun and adventure! He went as 'Rough Rider'. Pity we have no photo of this occasion!

In Jack's 1914 diary he writes of attending church on Sundays, usually the evening service. He also notes that he attends the 'pictures' on Wednesday nights and Saturday nights. He sometimes wrote of attending with a girl, but he never stated who he took!

On Sunday 18 January 1914, Jack wrote in his diary, "Girls stopped home." Two days later he makes the following notes: "Went to the viaduct Te Kuiti. Picnic Rose & Poppy etc. Went down in motor car." 'Rose and Poppy' refer to his cousins, Alice Emily Lydford (26 July 1885 - 28 Aug 1978) who was known as Poppy or Pop, and Elsie Rose Lydford (28 Sep 1886 - 3 Apr 1953) who was known as Rose. The picnic turned out to be a farewell gathering for Jack because he had just received notice that he would start his new job in Eketahuna later that week.

The day after the picnic, Jack packed up all his belongings, bade farewell to his family in Te Kuiti, and boarded the 2pm train to Palmerston North where he stopped by to see his mother, and older brothers, Alf and Bob. Jack wrote in his diary that he played cricket at Alf's home in the afternoon, and stayed the night at Bob's place.

Life in Eketahuna

We are not sure exactly why Jack decided to work in the small town of Ekatahuna but it may have been on the recommendation of Jack's brother-in-law, Robert Ashcroft who was working in the town as a plumber, and had a farm at Newman, on the outskirts of the town.

On Thursday 22 January 1914, which happened to be Wellington Anniversary Day, Jack arrived in Eketahuna to work at Hoar and Baillie, a sash and door factory owned by Albert George Hoar (16 Feb 1868 - 4 Aug 1954) and his partner, James Fraser Baillie (23 May 1864 - 19 Apr 1949). Both families were Wesleyan Methodists. Jack boarded with the Hoar family. Jack wrote in his diary that the day he arrived in town, Mrs Hoar welcomed him as Mr Hoar was out of town working on a job. Jack's boss, Albert Hoar, and his wife Monica Johanna Conway (1874 - 1967), had six children when Jack came to board with them. The eldest, Glenard (Glen) Albert Hoar (1899 - 20 Sep 1917), was about 14 years old, while the youngest was barely two years of age. Jack mentioned Glen a few times in his diary, including a time when the young lad brought a bike out to a job that he was working on.

During 1914, Jack helped to build a veranda for a house owned by Timus Fred Peterson (19 Nov 1886 - 4 Oct 1917), a single farmer of Danish descent. His property was on Putara Road, 22 kilometres outside of Eketahuna. Jack called the job, "Mr Peterson's tenure". Because the job was so far out of town, Jack camped out in the house while working on it. [Timus Peterson was killed during World War I.]

|

From the Auckland Weekly News 1917

|

Jack also did work for Arthur and Margaret Escott (dates unknown) who lived within walking distance from Mr Peterson, and built a shed for John Harrison (dates unknown), the town butcher. After this he removed a tank stand for Albert R D Dowsett (dates unknown), the railway clerk. The most time consuming job Jack did was for farmers, William and Grace Duff (dates unknown). It appears that he finished building their new home, demolished their old one, and constructed the stand for their water tank. Jack's diary offers scant notes about the different stages of the construction processes of each job and mentions some of the men that also worked on the building sites with him.

In his diary, Jack wrote about some earthquakes that were felt on the morning of Sunday, 8 February 1914. He also records details of his church attendance, visits to the pictures, drill training, day excursions to a mountain and a waterfall, and a time when he suffered from some painful boils. On 6 April 1914, Jack celebrated his 22nd birthday with a party arranged by Mrs Hoar. On a few occasions Jack was able to visit his mother and brothers in Palmerston North, and he spent some Sundays with his oldest sister, Elsie Ashcroft and her family on their farm.

The Approaching War

Jack followed the political developments in Europe very closely. On 1 August 1914, he wrote in his diary, "The war seems to be getting serious." The following week he wrote this note in the back of his diary, "Aug 6th. War with Germany seems to be getting pretty serious according to accounts of the paper. Flour etc has risen in price and things generally are getting dear."

Volunteering to the front

On Saturday, 8 August 1914, Jack completed his job for William and Grace Duff. According to his diary, he packed up his tools, took a photo of his work, then went to town to get his boots mended. As usual on a Saturday night, he attended the pictures.

The following Monday and Tuesday, he did some odd jobs around town, before heading off to Palmerston North where he met up with some of his family. No doubt Jack would have informed them of his plan to join New Zealand's Expeditionary Force. In his diary for 11 August 1914 Jack wrote, "Volunteered to the front."

On Wednesday 12 August 1914 the New Zealand government's offer to send Expeditionary Forces to join the war was accepted by the Imperial authorities. The war was on everyone's minds. That same day Jack promptly went to Masterton to have a medical exam. It appears from his diary entry for that day that the test was not completed for some reason. For a week, Jack moped around town until he received word to go to Pahiatua for his medical exam. On Wednesday 19 August, Jack returned to Masterton and after passing the medical, was officially sworn in as a member of New Zealand's Expeditionary Forces and sent to Palmerston North's Awapuni Military Camp to begin training.

The certificate below shows that Jack passed the exam to become a Sergeant in August 1914.

|

Proficiency Certificate for Non-commissioned Officers

awarded to J W Cobb, August 1914.

(Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland 2018)

|

|

John Wesley Cobb 1914

This photo may have been taken when he was promoted to the rank of Sergeant.

(Courtesy of J Henry) |

Recitation: Fall In

Jack was struck by the words of the pro-war poem Fall In written by British writer, Harold Begbie. He copied it down into the back of his 1914 diary (shown below) along with the following comment, "Recitation which I learnt off by heart as I consider it very good."

|

Poem, 'Fall In' by Harold Begbie, 1914. Stanzas 1-3

(Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland, 2018) |

|

Poem, 'Fall In' by Harold Begbie, 1914

Final stanza and a note by Jack indicating that he liked the poem and had memorised it.

(Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland, 2018) |

Fall In By Harold Begbie, 1914

"What

will you lack, sonny, what will you lack,

When

the girls line up the street

Shouting

their love to the lads to come back

From

the foe they rushed to beat?

Will

you send a strangled cheer to the sky

And

grin till your cheeks are red?

But

what will you lack when your mate goes by

With

a girl who cuts you dead?

Where

will you look, sonny, where will you look,

When

your children yet to be

Clamour

to learn of the part you took

In

the War that kept men free?

Will

you say it was naught to you if France

Stood

up to her foe or bunked?

But

where will you look when they give the glance

That

tells you they know you funked?

How

will you fare, sonny, how will you fare

In

the far-off winter night,

When

you sit by the fire in an old man's chair

And

your neighbours

talk of the fight?

Will

you slink away, as it were from a blow,

Your

old head shamed and bent?

Or

say - I was not with the first to go,

But

I went, thank God, I went?

Why

do they call, sonny, why do they call

For

men who are brave and strong?

Is

it naught to you if your country fall,

And

Right is smashed by Wrong?

Is

it football still and the picture show,

The

pub and the betting odds,

When

your brothers stand to the tyrant's blow,

And

England's call is God's!"

Jack wrote notes about some of the Military Training they did at the Awapuni Camp. They usually awoke at 6 am to the sound of the Reveille being played. After physical drills there were company parades, section drills, and sometimes long route marches and rifle shooting practice. Saturdays was washing day and on Sundays there was a church parade in the morning. When he had leave, Jack usually visited his family in nearby Palmerston North.

Troops expected to leave New Zealand within days of arriving at the military camp. Major Herbert Hart of the Wellington Infantry Battalion wrote in his 1914 diary that his men were frustrated at the delay and there were constant rumours going around the camp that they would not be sent at all.

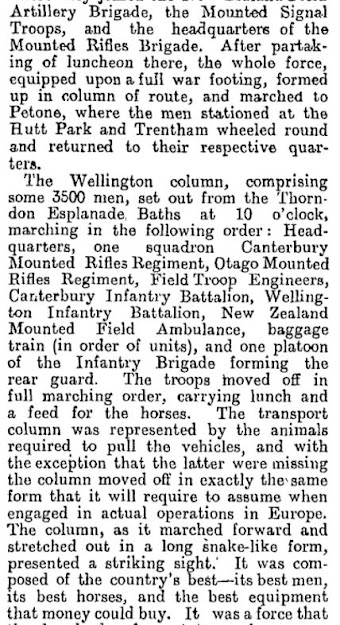

While troops were preparing to head off to the war, there were four steamships at the Wellington wharf being fitted out to accommodate soldiers as well as the horses of the Mounted Rifles Regiment. The plan was for these ships to join up with troopships from Auckland, Christchurch and Dunedin and sail together to join the Australian and British forces on the Western Front.

The Send Off

On Wednesday 23 September 1914, after five weeks of military training at the Awapuni Camp, the soldiers were transported by train into Wellington where the troopships were docked awaiting their arrival. Jack, who was part of the 17 Ruahine Company of the Wellington Infantry Battalion, was sent to troopship HMNZT No.10, (SS Arawa).

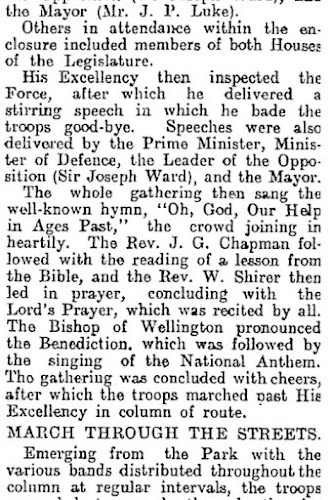

The next afternoon, the troops were marched to Newtown Park for the official send-off. The Governor General, Lord Liverpool inspected the troops, there were heartfelt speeches from various dignitaries including the Governor-General, the Prime Minister and the Mayor of Wellington, prayers and the singing of a hymn and National Anthem. A huge crowd of up to 30 000 Wellingtonians crowded the park and streets to watch the soldiers off. A light rain began to fall as the men marched back to the ships but it didn't stop the crowds cheering for their men.

The following comprehensive recount of the farewell for the troops was published in the Evening Post on 24 September 1914:

A short video showing some of the events of Wellington's official farewell can be found here. Here is a photo of troops lined up waiting to board the HMNZT No.10 (SS Arawa) after the official farewell.

HMNZT No.10 (SS Arawa) and two of the other troopships pulled away from the dock at sunset and anchored out in the harbour awaiting four sister ships from the South Island. They had planned on departing Wellington together in the early hours of 25 September and meeting up with the two ships from Auckland. Jack wrote in his diary, "A few ferry steamers visited us" during the night. Apparently, some of the men returned to the ship too late and had to be brought in by steamer!

Delayed departure

The departure didn't eventuate as planned, as the three ships from Auckland were recalled by Prime Minister William Massey. The book, New Zealand and the First World War 1914-1919 by Damien Fenton, explains that Prime Minister Massey was unhappy about lack of naval protection provided for the ships and requested more robust security. This meant that the three Wellington ships already in the harbour and the four ships from the South Island had no choice but to dock in Wellington.

In Jack's diary entry for Saturday 26 September, he wrote, "Rumours regarding German cruisers outside the heads. Still anchored out in the stream. Not much doing. Ferry steamers at times." Troops and horses remained onboard until the following Monday, when they disembarked and many were sent to various camps around Wellington. During the waiting period of three weeks, the troops participated in drills, long marches, shooting practice and mock battles. In the evenings there was plenty of entertainment available on shore, put on by the people of Wellington as well as talented soldiers.

As Jack was a Sergeant, he was held responsible for several duties including taking his turn as ship's guard. During leave, he wrote that he would go to town. His diary mentions that he attended an event at the Opera House and the Town Hall and went to tea with a Mrs Good.

On Saturday 10 October, around 5000 troops from the Expeditionary Force were marched all the way to the Lower Hutt Racecourse where they were inspected by the Governor General, then marched back again. Jack recalled in his diary that it was an extremely windy day and that there was a hurricane at night. An account of the day was printed as follows, in the Evening Post, 10 October 1914:

Dr William Aitken, in recalling this particular day wrote in his diary that when the men returned to their camp they found that all of the marquees and many of their tents had blown down in the wind.

Off to the Front

Two armoured cruisers, the HMS Minotaur and HIJN Ibuki arrived in Wellington Harbour on 14 October 1914. The troopships from Auckland, SS Star of India and SS Waimana were escorted in by the warship, HMS Philomel.

A huge crowd of people gathered in Wellington to see the boats off, including Jack's brother, Bob. Jack wrote in his diary, "Spent morning in town. Large crowds to see the boats off. Wrote some letters. Saw Bob etc." Dr William Aitkin, in his diary, also wrote of the cheering crowds on the wharf, that the band played, 'It's a Long Way to Tipparary' and that many women were in tears at the departure.

|

Wellington Infantry Battalion embarking on HMNZT No.10, Arawa. October 1914.

Photograph taken by S C Smith. Ref: PA1-f-022-6-1.

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23073352 |

The SS Arawa, with her load of 1318 men (including 59 officers) and 215 horses left the wharf at 4 pm and anchored out in the harbour with the other troopships. They stayed there until 6 am on 16 October when the HMS Minotaur followed by the HIJN Ibuki and the cruiser, HMS Psyche steamed down the harbour. The ten troopships (all freshly painted grey) and the cruiser HMS Philomel followed on behind, making a long line of 14 ships. A panoramic shot of the ships in Wellington Harbour can be found on the webpage here.

Thousands of Wellingtonians got up before dawn and went to various vantage points around the Wellington Heads to watch the fleet set off. It must have been quite a sight to see. After the ships made it through Cook Straight the troopships re-organised themselves into two lines. The HMS Minotaur heading the fleet, the HIJN Ibuki and HMS Philomel on the flanks, and the HMS Pysche bringing up the rear. And so, the Main Body of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force began their journey to Hobart to meet up with the Australian troops.

The following videos may be of interest regarding the departure of the Main Body:

Journey to the Front

As soon as the New Zealand transports reached the open sea, many soldiers became sea sick, including Jack. In fact, the first drill session of the voyage was cancelled because too many were unwell. Once everyone was accustomed to being at sea, a daily routine was established whereby soldiers would be kept busy. According to Major Hart's diary, the routine was typically as follows:

6:00 am Reveille

6:30 - 7:00 am Physical drills for soldiers

7:00 - 7:30 am Physical drills for officers

8:00 am Breakfast

9:00 am Squad drill

10:00 am Rifle exercises

11:00 -11:30 am Lectures

11:30 am - 12 noon Signalling practice

12 noon - 2:00 pm Lunch

2:00 pm Squad drill

3:00 pm Rifle exercises

4:00 - 4:30 pm Lectures

4:30 - 5:00 pm Signalling

5:00 - 7:30 pm Dinner break

7:30 - 8:15 pm Class for future non-commissioned officers

8:30 - 9:15 pm Class for non-commissioned officers

8:00 - 9:00 pm Lecture for officers

Examples of topics lectured on board the SS Arawa included ship sanitation, personal hygiene, how to take care of your feet, typhoid, dysentery, venereal diseases, and military etiquette. In Jack's diary he notes that he attended a lecture on the position of NCOs (non-commissioned officers) relating to officers. Entertainment on board included boxing and wrestling matches, concerts put on by talented soldier-musicians, a troopship magazine full of humorous stories and witty jokes, and even some whale spotting from the decks! Jack's diary mentions washing day, church services on board and other significant events such as horses dying and having to be hoisted over the side of the ship to their watery graves.

On Sunday 25 October 1914, Jack wrote about the first edition of the Arawa Lyre, the ship's magazine, in his diary. A copy of the inaugural magazine can be found here. It was a light-hearted magazine designed to entertain the troops on board. It appears that Jack paid a subscription of 2/- to receive the magazines.

Six days after leaving Wellington, the New Zealand fleet docked in Hobart, Australia. The following morning while the ships took on water and other supplies, soldiers disembarked and were taken on a three hour route march through the town. In the afternoon, when the ships departed from the wharf, many local women threw apples to the men on board.

The next stop was Albany, Western Australia where they arrived on 29 October 1914. Here the HMS Pysche and HMS Philomel left the convoy and were replaced by the warships, HMS Sydney and HMS Melbourne. 28 Australian troopships also joined the convoy. Earlier that day there had been a German led attack against Russian ships in the Black Sea. When the Ottoman Turks joined the war on the side of Germany, it led to an unexpected change of plan for the Australian and New Zealand forces. They would now head towards Egypt with the goal of defending the Suez Canal. There was a high level of disappointment among the troops about this change of plan as they had anticipated front line action in Europe.

The demise of the SMS Emden

As the convoy headed northwards towards Colombo, Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) they were always on the lookout for German warships. The one most feared was the cruiser, SMS Emden as it had managed to capture or sink 27 ships within two months! The concern was justified because on Monday 9 October, the SS Arawa heard an SOS from the nearby Cocos (Keeling) Islands about an unidentified warship nearby. The armoured HMS Sydney set off at full steam towards the Cocos Islands where it attacked the SMS Emden and forced the captain to run his ship aground rather than let her sink. Jack happened to be Deck Sergeant on the SS Arawa that day. He wrote in his diary, "HMS Sydney ran 'Emden' ashore... Cocos Islands. Great excitement. 2 killed 13 wounded HMS Sydney. Very warm. 88 degrees shade."

An accident

As the ships approached the equator the troops, including Jack, began sleeping up on the deck as it was much cooler there. On Friday 13 November 1914 Jack spent much of the day reading and writing letters and Christmas messages as it was a rainy, windy day. The same day the ship finally crossed the equator. For the troops on board the SS Arawa this was a reason to celebrate. They set up a pool made from one of the ship's sails which they propped up between the ship's hotel and the horse boxes. There was about one metre of water in it. The men began throwing each other into the pool until they had all been dunked. Some officers also jumped in voluntarily but some were carried to the pool and dunked. Lieutenant Ernest J H Webb (32), one of the ship's doctors, was one of the last officers to be dunked but unfortunately dived in and hit the bottom hard, breaking his neck. He was paralysed immediately.

Colombo

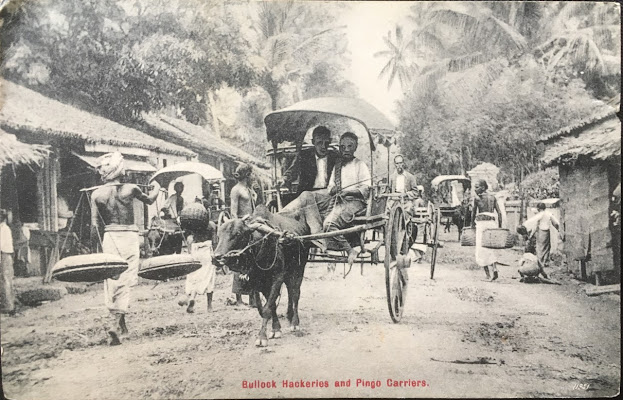

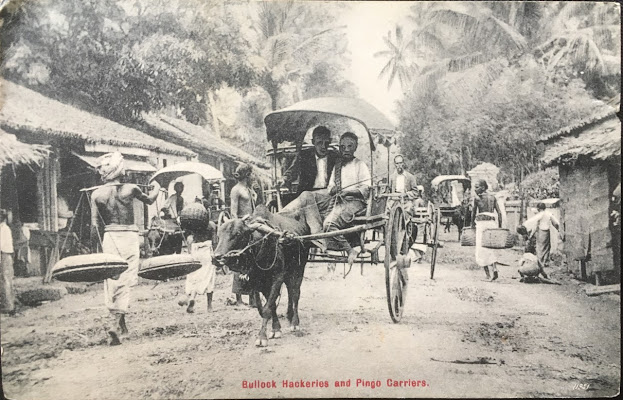

On 15 November 1914, the ships docked in Colombo. Dr Webb was taken off and sent to a local hospital. Sadly, he died a few days later. Some of the troops, including Jack, got leave to go ashore twice. Jack wrote in his diary that he took a few rickshaw rides. He also managed to buy a few souvenirs including curios and shoes.

|

Postcard that Jack bought in Colombo, 1914

(Courtesy of J Henry) |

|

Message on the rear of the postcard Jack bought in Colombo 1914

(Courtesy of J Henry)

Wishing you the compliments of the season"

and hope this Exmas [sic] will be the best you have had.

Love to all and good wishes

from John W. Cobb Sgt. xxxxx |

|

A small box Jack bought in Colombo 1914

(Courtesy of J Henry) |

After taking on water and coal in Colombo the ships left the port on Tuesday 17 November 1914. 33 of the German prisoners from the SMS Emden had been brought on board the SS Arawa. Jack took his turn to mount a guard over them the first few days they were on board. In his diary, he wrote that he received some coins. These coins where probably canteen tokens marked 'Emden' and were traded by the prisoners for cigarettes. On Wednesday 18 November Jack wrote the following notes, "On guard. Prisoner's meals. Potatoes peeling."

The nine day journey to Aden was relatively uneventful. During it Jack undertook his share of deck duty, attended a memorial service for Dr Webb, was given two typhoid inoculations which made him feel ill and was issued with identification tags. After 24 hours in Aden, the convoy sailed through to Suez where the prisoners disembarked. It was here that the troops learned that instead of going to England, they would be heading to Egypt.

Prior to proceeding through the Suez Canal, each ship was given a search light and had to pile up sandbags on the decks and mount their machine guns on the starboard side in case of attack. The convoy passed safely through the Suez Canal and reached Port Said where the ships were again coaled. After one further day of sailing, the SS Arawa docked in Alexandria, Egypt.

Egypt

The SS Arawa reached Egypt on 3 December 1914 and the troops were sent to Zeitoun Camp. Here are two of Jack's diary entries of note:

Friday December 4, 1914

"We were marched ashore at Alexandria today through ill smelling streets, fine buildings, moorish domes. We left Arawa. Entrained for Cairo. No tea & bivouacked the night [in the] desert. Cold.

Saturday December 5, 1914

"We lined up at 6 am & received a roll & a cup of cocoa each. Breakfast ration. Pitched tents etc. 2 biscuits. Dinner rations. Detailed off into tents. No. 16 tent. Only temporary places. More men arriving into camp. Went across to [the] canteen [at the] Tommies [sic] lines."

While in camp in Egypt, Jack and his comrades in the Wellington Infantry Battalion received further military training under Lieutenant-Colonel William G Malone (24 Jan 1859 - 8 Aug 1915). He is described in Richard Stower's book, 'Bloody Galipoli' as being a hard taskmaster but well liked and respected by those under him. Lieutenant-Colonel Malone trained his battalion in the desert, away from the other battalions. Part of the training involved physical drills (known as physical jerks) which were done before breakfast. After battalion parades there were 5-6 kilometre long marches into the desert. Further drills, including shooting practice and mock battles, were undertaken there before the troops were marched back to camp. Full packs and lunch were carried on all the marches. A short video showing New Zealand troops in action in Egypt can be seen here.

Jack's diary for Wednesday 23 December 1914 read: "Reveille 5:30. Parade 8:30 am. Regiment marched through Cairo all armed. Ammunitions. BOS stayed in camp on duty. Lost belt & bayonet. RO Sergt." This parade of around 10 000 troops, each with 20 rounds of ammunition was held on the occasion of the crowning of Prince Hussein Kamel Pasha as Sultan of Egypt. Troops paraded through the bazaars and residential areas of Cairo, then after a ten minute lunch break, they were marched back to camp. It was to impress the local population of the power of the military in their midst should they decide to side with Turkey.

Leave in Cairo

When soldiers were on leave there was plenty to do! They could catch a tram (and some rode donkeys) about 10 kilometres to the city of Cairo for fine dining at bustling hotels, restaurants or soldier's clubs such as the YMCA's Ezbekiah Gardens. In his diary Jack mentions taking tea at the Bristol Hotel, and dining at the Soldier's Club. There was the Cairo Museum housing mummies of Pharaohs, the theatre, and the market to visit. Soldiers purchased many kinds of souvenirs to send back home. Jack bought this fly swat made from carved ivory and horse hair as a souvenir.

|

A fly swat made from carved ivory and horse hair once owned by Jack.

(Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland 2018) |

There were other interesting things to do around Cairo. Soldiers could visit the Giza Zoo, Luna Park (an amusement park), and also see the Virgin's Tree, an ancient tree under which the Virgin Mary is supposed to have rested with baby Jesus during their flight from Egypt. Jack visited this tree and took a twig off it and wrapped it up with the explanatory note shown below. Unfortunately, the twig has been lost! More information about the Virgin Tree, including photographs, can be found here.

|

Note that once accompanied a twig from the Virgin Tree.

(Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland 2018) |

The top of most soldier's list of things to do in Cairo was to visit the Sphinx and the pyramids. In his diary, Jack mentioned visiting the pyramids twice. He climbed the Great Pyramid (also known as The Pyramid of Khufu or The Pyramid of Cheops) on 26 December 1914. We believe he is the soldier shown back right in this group shot:

|

This photograph was clipped out of the Auckland Weekly News, 11 March 1915 p36,

and shows some New Zealand soldiers on the top of The Great Pyramid of Giza .

It is believed that Jack is pictured in the back right of the group.

Unknown photographer

(Courtesy of J Henry) |

Christmas in Egypt

On Christmas Day 1914, Jack wrote in his diary, "Breakfast 7:30. Church parade 9:30. Rest of the day free. Had my photo taken. Went to Giza Zoo. Had a look around. Visited the "Karsall" Opera [probably the Kursaal Theatre] at night. Bed 11:30 pm."

Giza Zoo was the first zoo to be opened in the Middle East, established in 1891. Soldiers who visited were often impressed not only with the variety of animals it housed but even more so with the beautiful botanical gardens that surrounded them. When Jack visited, he may have been one of the first to visit the Animal Museum which was established in zoo complex in 1914 and featured mummified animals and skeletons.

The Kursaal Theatre, in the Ezbekiah district of Cairo, had a casino and music hall where a variety show would be staged for the troops. The show would include juggling, trick cyclists and dancing girls from England.

On Boxing Day Jack wrote, "Breakfast 7:30. Leave till 1 am Sunday. Took early train for Cairo then the car for the pyramids. Very crowded. Went to pictures in the evening. Returned by train 10:30 pm. Climbed the large pyramid."

More training

After some extra time off over Christmas, the troops got back into training. They continued to go on marches into the desert where they would do drills, dig trenches and engage in mock battles. On New Year's Eve, Jack wrote the following:

"Thursday December 31, 1914

Breakfast 7 am. No parade till 1 pm. Went on a march. Heavy marching order on the desert. Field work. Infantry in attack on some trenches. It was very warm work. 4 pm to 5:30 pm. We had some outpost work. We had tea after 7:30 pm. We did outpost work. Dug trenches and I was in the picquet. We stayed in the trenches for 3 hours. Very quiet. The enemy (13-14 platoons) broke through outr group about 12:15 am and then we finished operations. We then marched back to camp arriving at 2:30 am New Year's eve." According to the diary of Dr Aitken, men from the Ruahine Company played the bagpipes as they marched back into camp!

Defending the Suez Canal

The New Zealand Infantry Brigade were sent to the Suez Canal on 25 January 1915 where they were to protect the area from Turkish attack. Jack's Battalion was stationed at an area known as Kubri. While Turks attempted to cross the canal on 2 February, soldiers from the Nelson Company fired on them, sinking most of their boats and inflicting many fatalities. The following night, the Turks fired artillery towards soldiers of the Wellington Infantry stationed. This was New Zealand's first real taste of war. Another was just around the corner.

By the end of February 1915, the Battalion returned to their camp in Zeitoun, and spent the weekend enjoying themselves in Cairo. No doubt, Jack used the opportunity to send mail, including the postcard shown below, to his family.

|

Jack sent this postcard to his sister, Dorothy Blackman. in Te Kuiti, New Zealand

(Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland 2018) |

|

Rear of the postcard Jack sent to his sister.

(Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland 2018)

16-2-15 Dear Dorothy, Just a line to let you know that I am well and keeping in good spirits. I am still looking for a letter from you and I hope you are well. The weather is very warm here now but the trouble is we cannot get a decent wash. I haven't been able to sleep with my boots and clothes off for 3 weeks. Love to all. Jack. |

In this excerpt of a letter (below) written to his sister, Dorothy, Jack mentions the full military inspection by British General, Sir Ian Hamilton (16 Jan 1853 - 12 Oct 1949). He also mentions an inspection by Major General, Sir Alexander Godley (4 Feb 1867 - 6 Mar 1957) and Jack Hughes - Major John (Jackie) Gethin Hughes (13 Mar 1866 - 23 July 1954). The Cobb family would have known Jack Hughes because he lived in Napier for many years, from around 1888 until he went off to the South African (Boer) War. At the time this letter was written, Jack Hughes had just been appointed Camp Commandant of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in Egypt.

|

Excerpt of a letter that Jack wrote to his sister, Dorothy.

It was written in the first week of April 1915.

(Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland 2018)

... to be left at the base so I will take good care that I am not. Last week General Sir Ian Hamilton inspected us here and we did the march past. You have no idea of the dust that was caused as we were marched over soft sand. I had my photo taken and you can see the dust on our faces. We had full marching order dress and in the hottest part of the day. The Maoris are camped opposite to us, and the other night General Godly visited them and the Maoris gave hakas and songs etc. Jack Hughes was there and he called for 3 cheers for the Maoris after they... |

At the beginning of April, troops were given notice that they all, apart from the Mounted Units, would be departing for the front line the following week. Those proceeding to the front were pleased and began practicing packing their kits and spent time around a large grindstone, sharpening their bayonets.

On 10 April 1915, they left camp. The Taranaki and Ruahine Companies plus two companies of the Canterbury Battalion (550 men and 18 officers) were led by Lieutenant Colonel William G Malone. They boarded the ship, HMAT A50 Itonus in Alexandria. The Hawke's Bay and Wellington-West Coast Companies along with the Signallers, and Machine Gun Section (513 men and 17 officers) were led by Major Hart and boarded the ship, SS Achaia. The ships departed on Monday evening, 12 April 1915 and set off for the port of Mudros on the Greek island, Lemnos, arriving three days later. The men were given maps of the Gallipoli Peninsula to study on the voyage so that would be familiarised with the place they were heading to.

The port and harbour in Mudros was crowded with ships and submarines, which must have excited the boys from down-under. It was here that the Australian and New Zealand forces first came together as the ANZACs (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) and joined 80 thousand men from Britain and France (known as the combined Allied Army in Turkey or Mediterranean Expeditionary Force) under the overall leadership of the British General, Sir Ian Hamilton.

While in Mudros, the Anzacs practiced climbing up and down the ship's rope ladders with all their gear, and participated in other drills to simulate the planned boat landings on the Gallipoli Peninsula.

The Battle of Gallipoli

The plan was for the Anzacs to land on the beaches and move inland in order to capture the Gallipoli Peninsula for the Allies. The campaign to rout the Ottoman army from the Gallipoli Peninsula began before dawn on Sunday 25 April 1915. The Australians set sail first and reached the beach now known as Anzac Cove at approximately 1 am. The plan was to land at Z Beach but unfortunate errors led to the troops landing about one mile north of the intended beach. This was a catastrophic mistake, as the rugged and steep ridges only favoured the Turks who were perched on top and could fire mercilessly down on the unprotected Anzacs as they landed on the beach. Anzac troops who survived the landing had to move quickly to find cover or they too would succumb to the Turkish bullets. There were hundreds of casualties.

Landing on the Gallipoli Peninsula

Jack, with his Ruahine Company arrived near Gaba Tepe off the Gallipoli Peninsula on board the transport ship SS Lutzow about midday on Sunday 25 April 1915. The men onboard were unable to land immediately due to heavy fire from the Turks. All afternoon the men would have just watched the battle from the ship. Finally, by early evening Lieutenant-Colonel Malone and one company of the Wellington Infantry Battalion landed, stationing themselves as reserves under some cliffs on the beach. By 6 pm the rest of the Battalion had come ashore. The Wellington Infantry Battalion War Diary stated, "The enemy were raining shells whilst the landing was being carried out."

The Ruahine and Taranaki Companies bivouacked in a gully. During the night, the Ruahine Company and two platoons of the Taranaki Company made their way to a valley on Plugge's Plateau and entrenched themselves alongside the Australian troops that had already made their way there. All day long sixteen Turkish battalions fired on them from above, trying to drive them back to the coast. The Anzacs were able to stand their ground and the Turks suffered greater losses. During this attack, Jack received a gunshot wound to his left thigh.

Wounded

On 12 May 1915, Jack wrote a letter to his uncle, William Day who lived in Bournemouth, England. It was printed in the Bournemouth papers and re-printed in the Manawatu Standard on 23 July 1915. In it, Jack gives the detail about the Gallipoli landings and the incident in which he was wounded.

Recovering in Egypt

Jack, along with many other wounded soldiers, were evacuated by ship and taken back to Egypt. On 2 May 1915, Jack was brought to the 1st Australian General Hospital in Heliopolis, in suburban Cairo. This hospital was really a converted 400 room luxury hotel which was used by British forces during both World Wars. Interestingly, after the hotel was renovated in the 1980s, it became one of Egypt's presidential palaces. Images of the hospital in the Heliopolis Palace Hotel can be found here.

|

Patients from Gallipoli in the No. 1 Australian General Hospital

housed in the Luna Park skating rink, Cairo. c1915.

(Australian War Memorial) |

|

Operating Theatre and staff at No. 1 Australian General Hospital

located in the former Heliopolis Palace Hotel, Cairo. c1916.

(Donor: G Pearce. Australian War Memorial) |

|

Luna Park at Heliopolis which was converted to a hospital in 1915.

(Australian War Memorial) |

|

Patients in the dining hall at the No. 1 Australian General Hospital, Luna Park, April 1915.

(Australian War Museum)

|

|

John Wesley Cobb 1915

Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, AWNS19170628-40-7

|

|

Sergeant J W Cobb, wounded

Otago Witness, 2 June 1915

|

The following grainy photo of Jack appeared in The New Zealand Free Lance on Friday 14 May 1915 along with the names of some of the other soldiers killed or wounded at Gallipoli. |

Sergt. J. W. Cobb (Palmerston North),

Wellington Infantry; wounded

Free Lance 14 May 1915

|

After a six week stay in hospital, Jack was sent to a Convalescent Camp in Helouan, about 32 kilometres up the Nile River from Cairo.

|

Al Hayat Convalescent Hospital, Helouan.

(Australian War Museum) |

Jack spent just over one month in Helouan recuperating. The following postcard was sent to Jack's brother, Bob, from the Hotel Al Hayat Convalescent Hospital in Helouan:

%2BWesley%2BCobb%2B(2).JPG) |

Jack Cobb after his discharge from hospital in Cairo. 1915.

(Courtesy of G J Bland) |

|

Message on the back of the postcard Jack sent to his brother in 1915.

(Courtesy of G J Bland)

Hotel 'Al Hayat' Convalescent Hospital Helouan Dear Bob, Just to let you know I am well out having plenty of rest etc about 40 miles from Cairo's noise. I have received no mail yet but still in hopes. I hope all are well. I have recovered my lost property and have managed to get some pay. Now with best love to Alice & children & hoping business with you is good. I remain yours etc Jack I had photo taken one night the first day out of the Hospital at Luna Park. I had no clothes, but I borrowed an Australian's uniform sooner than be beat. |

On 19 July 1915, Jack was discharged from hospital and sent back to the Zeitoun Camp but it appears that he had not fully recovered from his injuries because he was re-admitted to another convalescent hospital on 31 July. This time, he spent one month at the Sidi Bishr Convalescent Hospital in Alexandria. It is likely that during this time, Jack was permitted to venture around town a little. Below is a photo of his Services Guide to Alexandria:

|

Serviced Guide to Alexandria

(Courtesy of G J Bland. Photo by K Bland 2015) |

Return to Gallipoli

On 28 August 1915, Jack rejoined the Wellington Infantry Battalion in Gallipoli along with some fresh troops, relieving some weary and sick men who were sent off to the rest camp in Lemnos. At this time Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Hart took command of the Wellington Battalion which was severely depleted and numbered just over 250 men. The Wellington Battalion took turns being stationed at the front line, at Rhododendron Ridge and at the Apex. Troops were always busy at the front line. All supplies had to be brought up on donkeys or on foot. During the day the men would work to improve communication lines and the support trenches. At night, they would make wire entanglements and improve their cover positions at the front. They would always be at a heightened state of alertness because at some places the enemy was just 45 metres away and could hear their conversations!

Conditions on the Gallipoli Peninsula were terrible for the Anzacs. There was a lot to contend with - swarms of flies, rats, and lice, extremes in weather, a poor diet, limited supplies of clean water, the smell of the dead, lack of hygiene, disease, and on top of that, an ever-present enemy lurking above them.

From mid-September to mid-November both the Turks and the Anzacs dug in. They continually fired on each other, but the Anzacs had fewer casualties due to their improved trenches. The Anzacs spent most of their time improving their support lines and accommodations. They also extended and deepened their trenches and began to build an underground kitchen near the front line.

Mail from the front

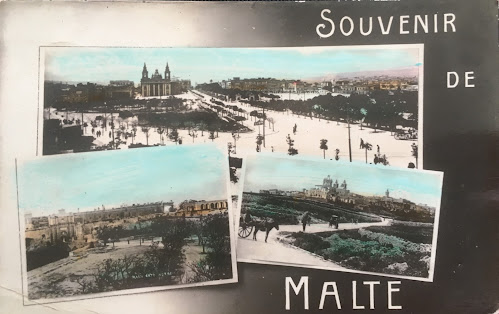

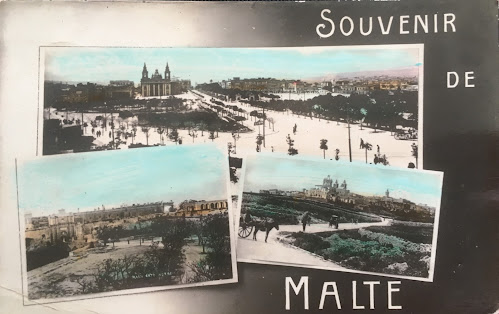

It appears that Jack spent some time on leave in Sarpi Camp, Mudros during October 1915. The postcards shown below were written there. It is unknown how he got the first postcard as have no record of him ever visiting Malta.

|

Postcard that Jack sent to his sister, Dorothy Blackman. 1915

(Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland 2018) |

|

Rear of the postcard Jack sent to his sister in 1915. (Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland 2018) Sapri Camp Mudros October 13th 1915 Dear Dorothy, Just a few lines to let you see I have not forgotten you. I have not heard from you, for some time now, so my mail must be delayed in Alexandria or elsewhere. I hope this finds the children all well. Give them my love and good wishes and say I have not forgotten them. The children we see here (Greeks) are very poor and they are always about our rubbish heaps picking out bread etc. Now with best love to all. From your affectionate brother, Jack xxxxx |

|

Postcard written to Jack's sister, from Mudros 1915.

(Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland 2018) |

|

Rear of the postcard Jack sent to his sister, Dorothy in 1915.

(Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland 2018)

Mudros, October 18th 1918 Dear Dorothy, Just a few lines to thank you for the parcel of envelopes, handkerchiefs, and the proofs which I received yesterday. I considered myself very lucky in getting it as it was handed to me with the outside paper which contained the address only, - the string was missing. I am sorry to say that the proofs you sent had faded but I could just about see who it was. I should very much like a P.C.(?) of it. There was a very big mail in. I got three parcels but no letters and none the last two times. I got a parcel from Maggie Nichols along with yours also one from Auntie and mother. Now I hope this finds you all well as it leaves me (not so bad) with best love and all good wishes from your loving brother Jack. |

|

Evacuation

Jack was appointed Temporary Company Sergeant Major in Gallipoli on 1 November 1915. He obviously had some natural leadership qualities. We know that he was well-liked by his comrades. The Ruahine Company, of which he was a part, took turns being in the front line.

In early November, troops who had been taken off the peninsula to rest were brought back. Life on Gallipoli was better in some respects but now the weather was the problem. The rain, wind and snow made conditions miserable.

After eight gruelling months, it was decided that the Allied Forces would be withdrawn from the Gallipoli Peninsula. According to the Wellington Battalion War Diary, the Ruahine Company were in No 3 Post from 11 December 1915. On 15 December, the diary noted:

"Today information was conveyed to all ranks that the ANZAC position was to be evacuated as speedily as possible." The news that they would be leaving the graves of their fallen comrades brought much disappointment.

In the few days leading up to the evacuation, stores and equipment were secretly moved offshore, buried or destroyed. Mines and traps were laid and all personnel who were even slightly sick or hurt were dispatched to awaiting hospital ships. On the evening of 17 December cunning devices were set up to fire shots from guns even after the soldiers had left. This was to fool the Turks into believing that nothing was amiss. Candles were lit, fires were left burning, and blankets were left out to dry in the sun. Everything seemed as per usual.

The main part of the evacuation was carried out at night. On the evenings of 18 and 19 December, soldiers made their way silently down to the main gateway at Chailak Dere where they were checked off before being taken to awaiting ships. The Hawke's Bay and Wellington-West Coast companies left first on 18 December. The Ruahine and Taranaki Companies remained at the front line. To trick that Turks into thinking that there were the same number of troops at the front, soldiers walked through the trenches, fired their rifles and threw bombs at various places. According to the Manawatu Standard, 30 August 1917, Jack was one of 15 men from the Ruahine Company who were selected to leave the trenches at the Apex last. By 4:10 am on 20 December, all the Anzacs were aboard the ships which sailed to Lemnos.

While the evacuation miraculously incurred no loss of life, the Gallipoli campaign was an Allied defeat. While the Anzacs were relieved to escape the horrors of Gallipoli they were bitterly disappointed to leave their dead with no one to tend their graves.

From Mudros to Moascar Camp

The Anzacs were taken by ship to Mudros East Camp on Lemnos where they were welcomed on shore by a Navy band. The Anzacs were delighted to take hot baths and to eat a huge breakfast after months of surviving on meagre rations and a limited water supply. After a few days of rest the New Zealanders boarded the SS Simla on Christmas Day. They were treated to a delicious Christmas dinner on board, complete with Christmas pudding!

The Anzacs arrived in Alexandria on 28 December but disembarked the following day, and entrained for the camp at Moascar, a short distance from Ismailia. On 1 January 1916 Jack was appointed Company Sergeant Major. He was now second in command of his platoon (50 men).

This is Jack's copy of the Ruahine Company Roll Book, dated 1 January 1916, and his badge. The Roll Book is opened to the page that shows his name.

|

Jack's copy of the Ruahine Roll Book dated 1 January 1916.

(Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland 2018) |

At this time, reinforcements from New Zealand had arrived to join the surviving Anzacs. A new round of training was put in place with daily marches into the desert, often at night, to harden up the troops and prepare them for front line duties in France.

Promotion

On 1 March 1916, Jack received another promotion. This time he was commissioned to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant and transferred to the 1st Battalion of the Auckland Regiment. Malcolm Scott Galloway 10/2146 (7 May 1887 - 19 July 1978), also from the Ruahine Company, was also promoted to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant that day. Both men can be seen in the following photo which was probably taken to commemorate the occasion.

|

Malcolm S Galloway (left) and Jack.

This was probably taken on the occasion of their promotion

to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant, on 1 March 1916.

Photographer unknown.

(Courtesy of J Henry) |

Preparing for the Front

At this time the Anzacs were re-organised into the I and II Anzac Corps, each having 60 000 men. They prepared to fight with the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front. The New Zealand troops initially became part of the I Anzac Corps consisting of the 1st and 2nd Australian Divisions and the New Zealand Division.

Before heading to the front line, Jack and the 1 Anzac forces spent 18 days defending a section of the Suez Canal. Then on 6 April 1916, Jack's battalion departed for France from Port Said on the ship HMS Franconia, managing to avoid the German submarines lurking about.

France

The 1st Auckland Battalion landed at Marseilles then traveled for three days by train up through France, skirting Paris, and finally arrived at Steenbecque on 16 April. Jack and his comrades were billeted out in the barns and pig sties of farmhouses located between the towns of Morbecque and Hazebrouck. Two of the biggest problems the soldiers faced on arrival was keeping warm and communicating with the locals. Gunfire from the front lines could be heard in the distance.

By the end of April, the entire 1 Anzac Corps had arrived in Europe and had gathered in towns in the North-West of France, near the trenches surrounding Armentieres. The 1st New Zealand Brigade of which Jack's Battalion belonged to, went to relieve soldiers at La Chapelle d'Armentieres. On arrival, they found that the trenches were in a state of disrepair so they worked on draining and repairing them.

Australian Tunnelling Company

From 28 May 1916, Jack was first attached, then later (from 18 August), he was seconded for duty with the 1st Australian Tunnelling Company. They worked in the vicinity of Railway Wood, Hooge Wood and Armagh Wood near Ypres.

Jack wrote the following letter from 'somewhere in France' on 7 June:

|

Jack wrote this letter to his sister Dorothy on 7 June 1916.

(Courtesy of J Henry. Photo by K Bland)

Somewhere in France June 7 1916

Dear Sister Just a few lines to let you know I am keeping quite well and I hope you are the same. I am now out of the trenches having my rest but we cannot get away from the noise of the guns. We had a little rain here yesterday which has made the place muddy again. Give my kindest love to the children not forgetting my God-child (Jack). Kind regards to Arnold, hoping he is well and best love from your affectionate brother. Jack xxx

|

Leave in England

In October 1916, Jack took leave and visited his mother's family in Bournemouth, England. While there, the following picture was taken at the photographic studio owned by his maternal uncle, William Day.

|

This photo of Jack was taken while he was on leave

visiting his family in Bournemouth during October 1916.

Photo by E Day & Son, 9 Lansdown Road, Bournemouth.

(Photo courtesy of J Henry) |

|

This side profile of Jack was probably taken by his uncle,

William Day, in October 1916.

(Courtesy of J Henry) |

While in Bournemouth, Jack not only enjoyed visiting with his uncles, aunts and cousins, but explored the town itself. He bought several postcards which he sent back to his family in New Zealand. This one shows the beach. Jack sent it to one of his nephews, six year old Frank Blackman.

|

Postcard that Jack sent to his nephew Frank Blackman. October 1916

(Courtesy of J Henry) |

|

Rear of the postcard Jack sent to his nephew, Frank Blackman.

(Courtesy of J Henry)

Dear Frank, I hope this postcard finds you well. I am quite well myself. I have not had your letter yet but it is coming on the big boat and will be here soon. I was on this beach when I was in England But I did not have a paddle in the water. How would you like to have a paddle here. Now love to Jack, Kenneth & Phyliss. Jack xxx |

|

Postcard of the promenade by the beach in Bournemouth. 1916

(Courtesy of J Henry) |

|

Rear of the postcard of the promenade

at Bournemouth beach. 1916

(Courtesy of J Henry)

16/10/16 Some promenade! Eh what! The huts on the right are rented by people and are furnished. Quite a nice place to have afternoon tea I guess. Bathing machines on the left. Yours etc Jack. |

Jack, his maternal aunt, Rose Seline Holder (2 Feb 1861 - 1930), and three unnamed cousins (possibly Rose's two daughters, Phyliss and Emily Holder, and Mabel Day, the daughter of his uncle, William Day) visited nearby Christchurch. It appears that Jack was shown various places around the city that were of significance to his family including what Jack described as "mother's church" (the Christchurch Priory) and the house where his parents lived and most of his siblings were born (a two-storey building at 20 Barrack Road).

|

Postcard showing the Christchurch Priory. 1916

(Courtesy of J Henry) |

|

Rear of the postcard showing the Christchurch Priory. 1916

(Courtesy of J Henry)

Somewhere in France 3/11/16 This is the place which you may remember but I don't think so. It is mother's church, and not very far from here I saw the same house which you & most of the others were born in. It is now a butcher's shop. Jack |

While visiting the Priory, Jack viewed the signature of the Kaiser William who had signed the cathedral's visitor's book during his visit in 1907. Jack bought the postcard showing the signature and sent it to his brother-in-law, Arthur Blackman commenting on the unassuming nature of the signature.

|

Postcard of the Kaiser's signature, Christchurch Priory. 1916

(Courtesy of J Henry)

|

|

Rear of the Postcard showing the Kaiser's signature. 1916.

(Courtesy of J Henry)

France 3/11/16 Dear Arnold, This is as you see, the Kaiser's signature. I saw the original in the Priory Visitor's Book when I was there. It's nothing flash is it. I took my aunt Rose & 3 cousins with me and we had a good look around. JWC |

Christmas wishes

The Christmas and New Year card, shown below, was issued by the New Zealand military in 1916. It is interesting to note the printed message inside the card, The tide has turned and it's Maori translation.

|

A Christmas Card Jack sent to his sister and her family in 1916.

(Courtesy of J Henry) |

|

Christmas & New Year card 1916.

(Courtesy of J Henry) |

Jack also sent this embroidered Christmas card to his sister and brother-in-law, in 1916. In his accompanying message, Jack mentions being transferred to his new company. This probably referred to his formal secondment with the Australian Tunneling Company which occurred on 28 August 1916.

|

A Christmas message from Jack to the Blackman family in 1916.

(Courtesy of J Henry)

May you all have a very happy Xmas this year &

I only wish I was with you but perhaps next time.

Jack. |

|

Rear of the Christmas card Jack sent to the Blackmans in 1916.

(Courtesy of J Henry)

France October 24th 1916 Dear Dorothy & Arnold, Just to wish you all a merry Xmas and a happy new year. My photos may be a little late but still I think you will like them all. I have just come into my new company and hope to go into trenches tonight. We are having some rough weather here now but still keeping fit and well. Hope to hear from you again soon, same address. So with the best of luck from yours affectionately. xxxx Jack

|

Hill 60

From 9 November 1916, the Australian Tunnellers took over the defence of the tunnels in Hill 60, near the village of Messines, Belgium. Hill 60 was a man-made hill consisting of layers of clay, sand and quicksand deposited in a huge mound after the Ypres to Comines railway line was carved out in the 1850s. Because the hill was an elevated location in an otherwise flat landscape, it was a strategic location for both the Allies as well as the German forces. Both sides fought hard for it.

It was vital for the Allies, that the Germans did not discover their tunnels, mines or detonator cables before the planned detonation the following year. While the tunneller's main job was to defend the tunnels and the two huge mines hidden in Hill 60, their important secondary job was to improve the ventilation and drainage of the mines. This was done by digging a deep shaft lined with metal. It was named 'Sydney'. From it, they dug further defensive tunnels from Hill 60, naming them after various other Australian cities, and created some dugouts for troops. No doubt Jack's experience as a carpenter came in useful when it came to lining the tunnels and galleries with timber supports. The tunnels were up to 2000 feet in length and the mines were laid between 50 to 100 feet underground.

New Zealand Tunnelling Company

Jack was attached to the New Zealand Engineers Tunnelling Company briefly, from 9 December 1916 until 3 January 1917. The tunnellers worked on the underground defence system under the city of Arras and did some of the preparation work for the Battle of Arras.

In the field

On 3 January 1917, Jack was at the infamous military camp at Etaples, at the northern tip of France. He was temporarily attached to the New Zealand Infantry and General Base Depot, and then re-joined the New Zealand Division in the field on 15 January. Two days later he was again part of the 1st Battalion of the Auckland Regiment as a member of the 1st Brigade who were taking turns with the 2nd Brigade to defend the Fleurbaix sector, at either Tin Barn Avenue or the J Post trenches.

By late February, the 1st Battalion were at the front line at Despierre Farm. Their first job was to fix the trenches which were in a state of disrepair. Trenches were often not deep enough and had poor drainage. There were also blockages in the communication trenches which the troops fixed. They reinforced barbed wire defenses in the area as well.

The 1st Battalion were moved around a lot during the next few months, first to Le Bizet, Nieppe, then Aldershot Camp, then as support, at Ploegsteert, and then to front-line duties at Hill 63. They also spent time at Plus Douve Farm. After that, they were sent back to Hill 63 for a few days before returning to Aldershot Camp. When not in the front-line trenches, the 1st Battalion spent most of their time at Ploegsteert Wood, digging and burying cables six feet down in communication trenches, in preparation for the offensive at Messines. This work was done mainly at night.

Preparing for the Battle of Messines

On 4 May 1917, the 1st Battalion were at the line at Wulverghem, but a few days later were relieved. On 8 May, the whole Brigade were stationed back from the front lines to begin training for the battle of Messines. The 1st Battalion were billeted in farms at Pradelles.

On 18 May, Jack and the rest of the 1st Battalion travelled by train from Bailleul to St Omer. They then marched eight kilometres further on, to the little village of Setques. For the next 12 days, the men attended a training camp near St Omer, to prepare them for the upcoming battle. The men were able to study and rehearse movements on a large clay model of the front lines at Messines. After daily training sessions the troops marched back to Setques and promptly stripped and bathed naked in the river in full view of the locals!

On 3 June 1917, Jack and the 1st Battalion were stationed as support at Hill 63, sheltering in huts and tents in the bush. Guns were firing all around them. The 1st Battalion were relieved on 5 June. They went back from the front lines to Canteen Corner and received fresh supplies of ammunition and other equipment, including a steel helmet and a respirator. Troops also had to carry two mill's bombs in their pockets, food, water, as well as either a pick or shovel. Jack and other officers were each given a detailed map which showed enemy trenches and targets. The trip back to their post in the trenches east of Hill 63 was laborious as all the trenches were a hive of activity. They reportedly arrived back just 30 minutes before zero hour.

The Battle of Messines

By 2 am on 7 June 1917, the troops were ready for the assault and the supporting tanks were put into place. Jack was stationed in the trenches, east of the town of Messines, with the 1st New Zealand Brigade, and alongside British and Australian forces. The New Zealand 2nd Brigade was stationed to the left and the 3rd Brigade, on the right. The 1st Brigade was at the rear.

The British detonated deadly mines directly under the German lines. 19 of the 21 mines laid deep in the underground tunnels exploded in split second intervals from 3:10 am. The explosions were deafening, and said to be the loudest man-made sound recorded at the time. Some reports state that they were heard in London! The explosions created huge craters which can still be seen today. The largest crater is now known as the Pool of Peace It is 129 metres across and 12 metres deep.

The explosions surprised the unsuspecting Germans, killing thousands of them and leaving the survivors in a state of disarray. Immediately following the blasts, the Allied forces climbed out of their trenches and advanced into enemy territory. The soldiers of the 2nd and 3rd New Zealand Brigades, along with their British and Australian comrades, stormed Messines by 7 am and claimed it, as the stunned Germans tried to gain their composure. Jack and his 1st New Zealand Brigade left their trenches at 3:55 am, followed on from behind, and then proceeded to go beyond the 2nd and 3rd Brigades into the village, forcing the Germans back. They encountered a gas attack in the valley so the respirators came in handy.

Jack and the 1st Battalion advanced to the right of Messines village, towards the road from Wytschaete where they attacked and captured several German trenches. This article, printed in the Thames Star on 8 September 1917 quotes a letter written by a member of Jack's platoon, Laurence (Laurie) Joseph Towers (14 May 1894 - 24 October 1950), to his parents, L Joseph and Emily Towers who lived in Thames. In the letter, Towers relates details of the Battle of Messines and the last moments of Jack's life.

|

This article shares details about Jack's last moments.

(Courtesy of J Henry; photo by K Bland 2018)

|

The newspaper article has been transcribed below:

From the Messines Front

The following interesting letter from Messines has been received by Mr and Mrs J. Towers, Thames, from their son at the front:

There have been great doings here lately, and long before this reaches you our attack and successful taking of Messines will be old news to you. Nevertheless I know that all I have to say will be very interesting, so right from the moment we left cap I will begin my story. "Half-past nine boys and all are ready for the battalion to move off." The order is given and in succession of companies we move along a pre-arranged route to visit Fritz. Well, everything goes on smoothly and we eventually reach the communication trench by which we were to reach our resting post. One of Fritz's shells killed a few of our boys before they got this far but of course one must expect a few accidents. Fritz had been using tear gas shells a lot, and during our walk we had to make use of our helmets nearly all the time, so you can imagine that for a while we did not feel too comfortable. At last, we were all in position and sitting down in the sap waiting for the starting time of operations. Everyone was smoking and laughing, while a few of the older hands were giving a few useful hints to the new chums. All of a sudden out of the semi-darkness comes lumbering along one of our big tanks, and it did look comical I can tell you. Up it crawls to our trench, sort of stretches its back, and with a grunt rumbles on its way regardless of shell holes or barb wire. When this little procession was over we knew that the time was drawing nigh for us to mount the bags, and take the open trail, and with God's help have a safe return. Time goes on, five, four, three, two, one, only half a minute to go, and then the ground shook and rumbled something awful, and simultaneously with the explosion of three mines away went the banging of our guns. Never shall I forget the sight of those mines exploding. It was great, and put a heart into the boys that did good. the order comes down, "Get ready, up and over," the dinks are moving. Mr Cobb moves us into position and away we go on our voyage. All excitement, yet eager to see what was doing. We were up and in Messines almost before Fritz had his barrage going, and only one casualty, I think. Here we halted for a blow, as all hands were in need of rest, being short of wind. Three big shell holes held the platoon, and there we waited for our own barrage of fire to lift and go on. But what of Fritz? Well, all I saw was the back of them going for their life, leaving whatever they had behind them with here and there a chap whose earthly troubles were all over. The dinks halted at the town and dug in, our crowd passing through them further on to our own objectives. It was that easy a chap might just as well been walking along Pollen Street at the Thames. Most of our casualties were our own fault, the boys not waiting for our own fire to lift, but going through it in search of Mister Hun. Time is flying, and we reach our goal, all well, and no sign of Fritz offering to fight at all, except with a machine gun, which did us no harm. Now I come to the worst part of my story, when I tell you how Mr Cobb was killed by our own shell. I had been with him right along from the start by his side, and many the joke we cracked on the way. Both of us were with our platoon machine gun section, and it was going to stop in a strong point so that when we halted Mr Cobb went on to tell his other sections their work, and where to dig in. Myself being a bit weary and dead thirsty stopped to have a drink and a slight rest. From what the boys told me Mr Cobb found his section, and was showing them where to dig in when the shell that caused his death, and that of two others, came along. They heard it whizzing, but of course took no notice, when suddenly with a roar it burst right amongst them, falling short by about four or five hundred yards. Mr Cobb was blown about twelve feet away, and the result of his wounds caused his death about half an hour later. He never regained consciousness. The shock stunned me and upset the whole company, he being such a universal favourite with all, and especially his own platoon. We buried him not far from where he was killed, and hope someday to give him a decent grave, but at such a time one has to do his best, and that is all. The digging in and consolidating our line had to be gone on with, so all hands hove to with a will, and in a short time we were ready for any shelling of the Hun that he could give us. Night drew on, and all hands, though dead beat, knew there would be no sleep, as Fritz might counter attack, and we were not going to retire. It was one of the longest nights I have put in, but we survived it, and with a small drink of water and a bite of bread we went on bettering our trench and making life a bit pleasanter. Before the night drew on the Australians advanced again, driving Fritz back again but receiving a few casualties in the encounter. Those boys are fighters, and stick like glue to each other, and their thoughts of danger are practically nil. Well, next day goes on and we snatch what little sleep we can during the day. During the morning Cyril Whitehouse popped by, and sang out "Good luck, Laurie." The next time I saw him a few hours later he was dead. From what I saw he was killed by concussion of a shell, and his death was instantaneous thank goodness. He was a good mate of mine and we were often together. His death will be a miss, for us old boys. Poor Jack Glessing was also killed, but I did not see him myself. We stopped in the line seventy-two hours, and old Fritz made himself very objectionable the last night, shelling us with naval guns, but however we all arrived home safe and sound, dead tired, sleepy, and full up of the war. Goodness knows how long this rest will last, not too long I guess, as we will be at it again I suppose. The 22nd Reinforcements are in France, so things are booming are they not."

Jack was posthumously promoted to the rank of Lieutenant. His military record says that the promotion applied from 11 May 1917.

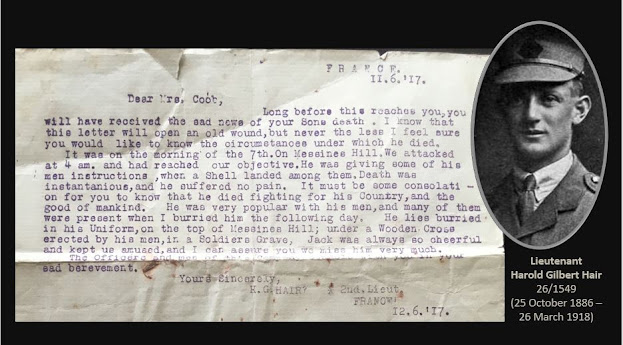

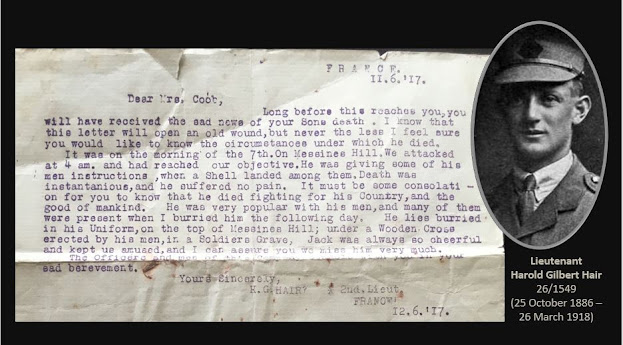

Following Jack's death, his mother received the following three letters from officers and a RQMS (Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant) of the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces. Each expressed their deepest condolences on the loss of Jack and all speaking so highly of him. The first letter was written by Lieutenant Harold Gilbert Hair (25 October 1886 - 26 March 1918) 26/1549. Lieutenant Hair was on the front line the day Jack died. He gave some first-hand details about the incident in which Jack was killed and indicated that he was the one that buried Jack on Messines Hill.

|

Letter written to Harriet Cobb from Harold Hair, on the death of her son, Jack. 1917.

(Letter courtesy of J Henry. Photo from the Auckland Weekly News 1918)

|

The letter shown below was written by 2nd Lieutenant Allan Percival Anderson (14 March 1893 - 4 July 1939) who attended the same school as Jack around 1898-99. He speaks of attending church services with Jack whilst they were in Egypt. At the time this letter was written, Allan was a Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant.

|

Letter written to Harriet Cobb from Allan Anderson, on the death of her son, Jack. 1917.

(Letter courtesy of J Henry. Photo courtesy of H Everitt)

The final letter was written by Major J. Gordon Coates (3 February 1878 - 27 May 1943) who was the MP for Kaipara and Prime Minister of New Zealand (30 May 1925 - 10 December 1928). In this message he recounts that prior to the battle, Jack gave him instructions to write to his mother if anything happened to him. Major Coates also expresses just how respected and loved Jack was by the men in his Company, and especially by those in his platoon.

|

|

Letter written to Harriet Cobb from J. Gordon Coates, on the death of her son, Jack. 1917.

(Letter courtesy of J Henry. Photo from Auckland War Memorial Museum - Tamaki Paenga Hira. PH-ALB-195-p83-3) |

Major Coates sent Harriet the last known photograph of Jack which was taken just before the Battle of Messines commenced. Here he is, seated in the foreground of the photo with other officers. Major Coates is seated behind him, in the centre. The names of the other officers are not presently known.

|

The last known photograph of Jack (front foreground) taken with other officers

of the 1st Battalion of the Auckland Regiment. cJune 1917.

Major J Gordon Coates is seated in the centre.

Unknown photographer. Copy by Charles J Allen's Studio, Palmerston North.

(Courtesy of J Henry.) |

Burial

Jack was 25 years old when he died. The men of his Company buried him in his uniform, in a soldier's grave on Messines Hill under shell fire. They placed a wooden cross on his grave and determined to give him a better grave at a later date. Sadly, this never eventuated. The exact location of Jack's grave is now unknown.

Remembering Jack

This notice of Jack's death was printed in the supplement to the Auckland Weekly News, 28 June 1917:

|

(From the supplement to the Auckland Weekly News 28 June 1917)

|

Two months after Jack's death, Private Gordon Charles Jones (19 Aug 1882 - 27 July 1974), who was a reporter in Gisborne prior to the war, wrote to his mother about Jack, speaking most fondly about him. Private Jones' father, a Land Court judge, forwarded a portion of the letter to Jack's mother in Palmerston North. The letter was printed as follows (newspaper source unknown):

|

(Courtesy of J Henry)

|

The following tribute to Lieutenant J W Cobb was first printed in the Bournemouth (England) paper on 7 July 1917, and then re-printed in the Manawatu Standard on 30 August 1917. It gave a summary of Jack's service during the war.

Other Tributes

Jack's sister and brother-in-law, Arnold and Dorothy Blackman, placed the following death notice for Jack in the New Zealand Herald, on 27 June 1917:

The Blackmans later had the following Bereavement Notice printed in the King Country Chronicle on 11 July 1917 to thank all those who sent them condolence cards and messages following Jack's death.

On the first anniversary of Jack's death (7 June 1918), his friend, Private W C Nicholson , from Te Kuiti, posted a memorial notice in the New Zealand Herald. It is likely that Private Nicholson, was Clement William Nicholson (8 Jan 1894 - 18 May 1955) who was born in Napier. In his memorial notice, Private Nicholson speaks of Jack's lonely grave far away and vows to always remember him.

It is clear that Jack was dearly loved by his family and that they felt awfully proud of him. Dorothy, in particular, was very public in her display of affection and remembrance of Jack. She placed the following memorial notice and quote in the New Zealand Herald on 7 June 1920, the third anniversary of his death:

Four years after Jack's death, Dorothy remembered in her brother in a more contemplative way. The memorial was printed in the New Zealand Herald, 7 June 1921:

Six years after Jack died (7 June 1923), Arnold and Dorothy Blackman again inserted a memorial notice in the New Zealand Herald, acknowledging that he gave his life in serving his country.

Military service

Jack served in the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces for a total of 2 years and 293 days. A summary of Jack's military service is as follows:

- New Zealand (training)

- Egypt 207 days

- Balkan (Gallipoli campaign and time in transit to hospital) - 21 days

- Egypt (in hospital and convalescent homes) - 114 days

- Balkan (Gallipoli campaign) - 124 days

- Egypt (training) - 80 days

- E E F Egyptian Expeditionary Force (defense of the Suez Canal) - 18 days

- Western Front - 428 days

To commemorate Jack's service, he was awarded the 1914-1915 Star, the British War Medal, and the Victory Medal. He earned one red and two blue service chevrons, and Wound Stripes (27.4.15).

|

Replica war medals for Jack:

1914-1915 Star, British War Medal, and the Victory Medal.

(Photo by K Bland) |

On 29 November 1921, Harriet Cobb was presented with a bronze memorial plaque and sympathy letter from King George V to acknowledge the sacrifice Jack made during the war. While the whereabouts of Jack's plaque and sympathy letter are known, the whereabouts of the scroll and medals aren't known.

|

Bronze plaque and sympathy letter presented to Harriet Cobb in memory of her son, Jack.

(Courtesy of J Henry; photo by K Bland 2018) |

Public Memorials

Jack's name is engraved on the Messines Ridge (NZ) Memorial, in the Messines Ridge British Cemetery, in Mesen, Belgium. This memorial remembers 828 New Zealanders who died in or near Messines in 1917 and 1918, and whose graves are unknown. Click here to see pictures of this memorial.

Jack's name is also engraved on several memorials in New Zealand, including the Auckland War Memorial Museum, World War 1 Sanctuary, as seen below:

|

Jack is remembered at the Auckland War Memorial Museum

(Photo by K Bland) |

|

Jack is remembered at the Auckland War Memorial Museum

(Photo by K Bland) |

Jack is remembered on both the Eketahuna War Memorial and the Te Kuiti First World War Memorial. Pictures of the Te Kuiti First World War Memorial can be found here.

|

Eketahuna War Memorial

(Photo by K Bland 2015)

|

If you visit the Palmerston North War memorial you will see Jack's name on the plaque. Click here to see pictures of it. His name is also engraved on the Roll of Honour at the All Saints' Anglican Church, 338 Church Street, Palmerston North, which was unveiled at a touching church service in 1920. Jack's name was not initially placed on this memorial (probably because he never lived in Palmerston North). According to an article in the Manawatu Standard on 15 December 1920, several names, including Jack's, were added to the memorial subsequently. Jack's name was probably added to this memorial because his mother and most of his brothers lived in the town.

|

Jack's belt

(Courtesy of J Henry; photo by K Bland)

|

|

Jack's identification tags and buttons

(Courtesy of J Henry; photo by K Bland)

|

|

Jack's paybook which was returned to his mother, Harriet, in 1919.

(Courtesy of J Henry; photo by K Bland)

|

|

(Courtesy of J Henry: photo by K Bland)

|

|

| (Courtesy of J Henry: photo by K Bland) |

Bibliography

Aitken, W. (1914-1915). Friends of the Hocken WW1 Transcription Project - Diary of Dr William Aitken 1914-1915), MS-1334/001. The Hocken Blog. Retrieved from https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/thehockenblog/friends-of-the-hocken-ww1-transcription-project-diary-of-dr-william-aitken-1914-1915-ms-1334001/

Annabel, Major N., (1927). Official History of the New Zealand Engineers during the Great War, 1914-1919.CEvans cobb & Sharpe, Wanganui.

Anonymous. (n.d.). History. Giza Zoo. http://www.gizazoo-eg.com/Content/ContentPage.aspx?pageId=2

Anonymous. (1897, December 18). Napier School Concert. Daily Telegraph. 2. Retrieved from http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DTN18971218.2.10

Anonymous. (1897, December 21). Prize Distribution. Napier Side School. Daily Telegraph. 3. Retrieved from https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DTN18971221.2.32

Anonymous. (1898, December 10). Annual School Concert. Hawke's Bay Herald. 3. Retrieved from https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HBH18981210.2.46

Anonymous. (1898, December 21). "Breaking up." Napier District Schools. Daily Telegraph. 3. Retrieved from http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/DTN18981221.2.25

Anonymous. (1902, August 8). Coronation. In New Zealand. Hawke's Bay Herald. 3. Retrieved from https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HBH19020808.2.18.1

Anonymous. (1903, December 10). Untitled. Hawke's Bay Herald. 2. Retrieved from https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/HBH19031210.2.11

Anonymous. (1910, June 4). Te Kuiti Volunteer Fire Brigade. King Country Chronicle. 2. Retrieved from https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/KCC19100604.2.7